“I am neither an owner here, nor a renter… I am just a lifelong guest…”

In The Dispossessed, the powerful women of Karadeniz gather under one roof, unveiling their immense strength that is usually hidden from the world. This intimate reunion takes place in a cosy family home, where these remarkable individuals showcase their resilience and determination. Witnessing the unity and unwavering spirit of these women is truly inspiring and serves as a reminder of the indomitable force within all of us. In the highlands, women live close to nature, working on their small lands, tending to their cattle and goats. They also enjoy spending time together in nature on their long walks together and in their family homes.

“Imagine a hometown where women don't have the right to own a house in the highlands, where traditions can sometimes surpass the law.

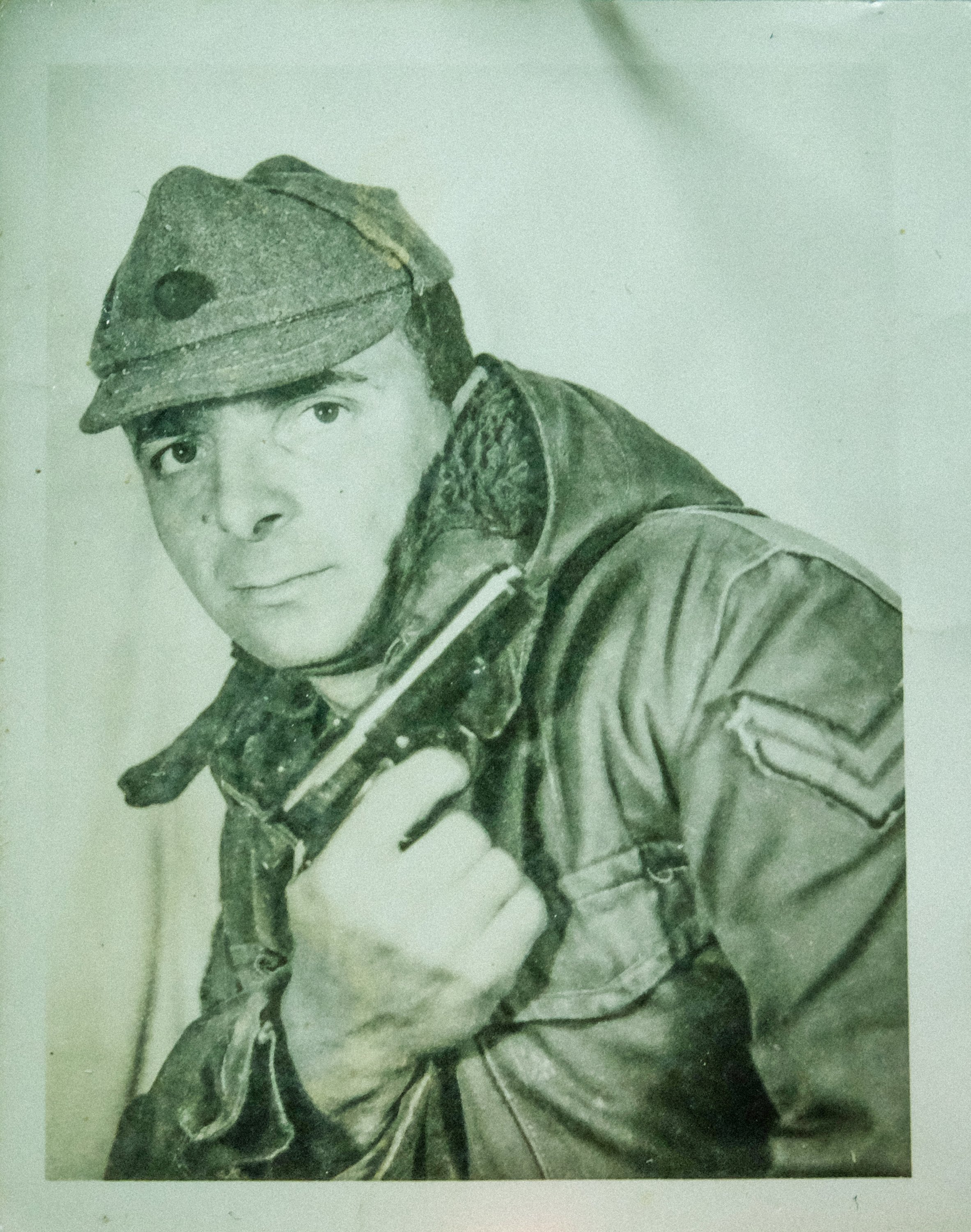

I grew up in such an environment, where generations have been portrayed through the eyes of male photographers.

I wanted to open a window into the portraits of the male population in the highlands and add my own female+ perspective, including portraits of women and animals,

thus saying 'we are here' to the memory of my homeland.”

Foam Talent Award 2024-2025, Exhibition Installation

Foam Photography Museum, Amsterdam, 2024

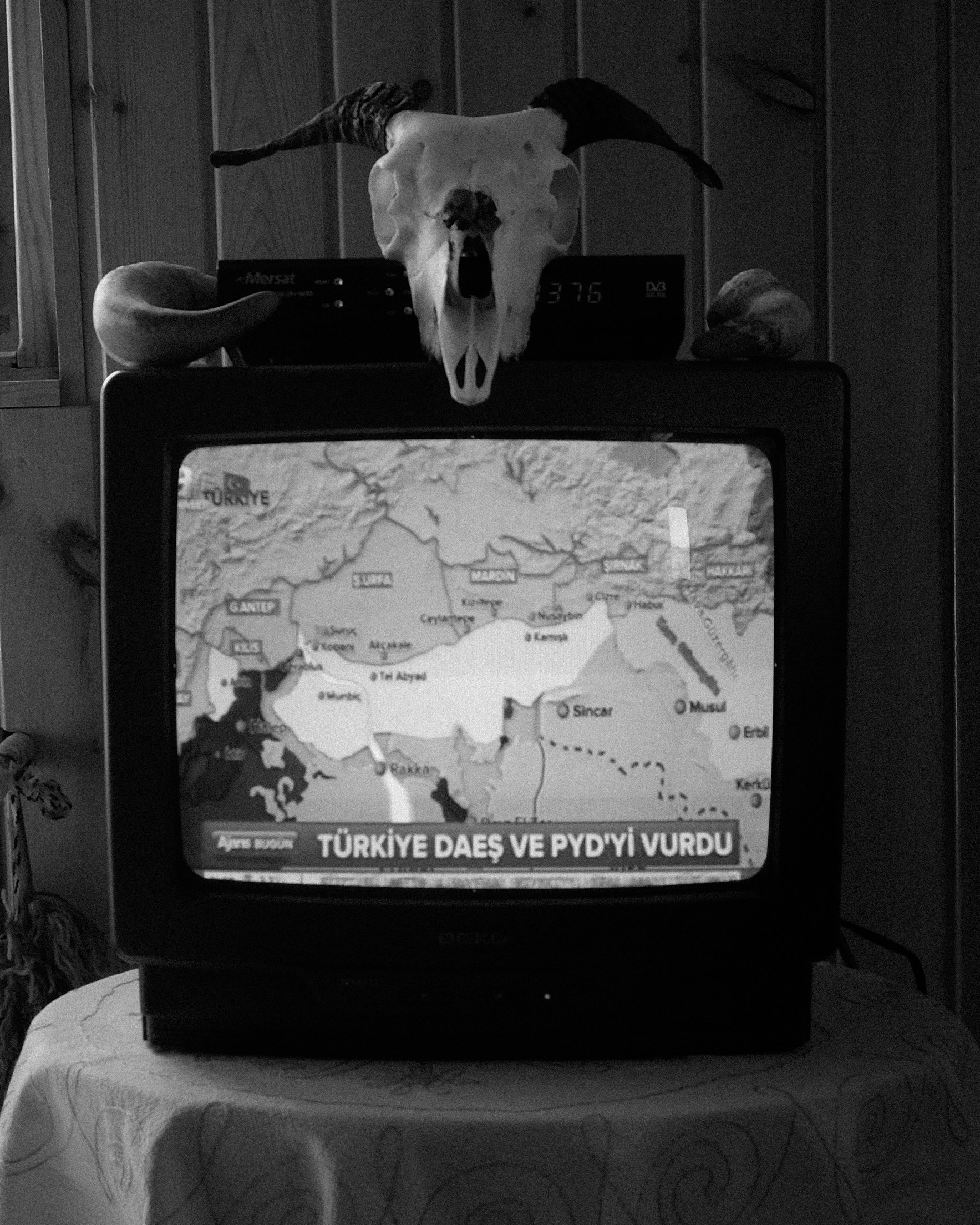

“Deep in a valley below the Kuşmer Highland, in Turkey’s Black Sea region, lies my village and homeland of Çaykara. As per tradition, women cannot own either house or land property on this highland

that right belongs solely to men.”

Such is how Cansu Yıldıran begins conveying both the biographical and social background of The Dispossessed, as if telling the first lines of a fairy tale. In fact, this fairy-tale language may seem very much appropriate, at first glance, in order to depict the artist's highland homeland, which they have visited every summer since their childhood after their family emigrated many years ago. With their camera pointed at Kuşmer, the place where their extended family, distant relatives and neighbours, plants, animals, orchards, trees, houses and their own childhood reside, Yıldıran attempts to make sense of life on the highland, and their own place within it. These photographs, which they took in Kuşmer, where their family does not possess even the slightest planted tree, tell the story of how women, animals and the land itself come to grips with the forces of dispossession, leaning on patriarchy and the institution that is private property. Thus, Yıldıran's gaze turns the highland into a disquieted landscape, and the human and non-human creatures that live there into grotesque bodies. Faces shining for only a brief moment when the flash goes off into the darkness of night, and bodies bent and twisted out of shape amid the rugged landscape, steer our gaze towards Yıldıran's personal nomadic history.

For all its beginning as though a fairy tale, this story soon proves uncannily evocative of the atmosphere of folk horror films, the sub-genre most suiting our time and age. For these lands rest on not one but several layers of historical dispossession which, despite remaining unspoken to this day, continue to stalk the present. Although administratively comprised within the provincial borders of Bayburt, Kuşmer is deeded to 373 households residing in the village of Şur (Şahinkaya), in Çaykara, kilometres away. Draped in the array of rights and powers vested upon them by the modern private property regime, not the least of which being the expulsion of others, the owners prevent those who, like Yıldıran's family, emigrated from the village, from acquiring land or houses on the highland. Hand-in-hand with the private property institution, this patriarchal order, officially termed “the set of rules and traditions, customs and sanctions having the force of law, specific to” Kuşmer, also forbids women from acquiring property on the highland. The purported common owners of the highland form a community of men, who mow the hay and share it in equal parts amongst themselves.

Yıldıran turns their gaze towards the daily life of women, plants and animals who live under this masculine property law. In doing so, they seek to find out what else women dispossessed and animals put to work by patriarchy, private property, the market and the State all working hand-in-hand, can do apart from acquiring property on a land that has been put under the yoke. Between the cattle and humans, appearing so intertwined as to have become indistinguishable from one another, clipped animal hides, which have merged with the grass, and women's bodies, disfigured by years of bending over the soil, something like an alliance is formed. This common existence heralds the nearing day when the perpetrators of dispossession themselves will be dispossessed, and the tide will eventually turn: that day will come, the day of the women, and other living beings, who pray, tend to gardens, care for animals, and collect immortelle flowers.

In spite of all the harsh conditions, violence, destruction, inequality and impoverishment strategies which they face, the women of Kuşmer do find a different way to take root in the land, other than property. They thwart the forces of dispossession’s violence, not by “standing upright”, but instead by bending over, down to the level of soil, the plants and animals. These women, carrying stacks of hay higher than themselves on their backs until turning into “hay women”, marching behind the animals, forming a line on the road, merging with the landscape while reciting their prayers, wearing calicoes of all sorts of colours and shapes, perform the art of existing by lodging themselves into the land and amid interspecies relations. In other words, in order not to break against the forces of dispossession, one must stretch, bend, and become disfigured. As pointed out by feminist researchers, despite their constituting the most vital discoveries made by humanity, because their inventors are purported to have been women, such practices as sowing, tending, reaping, storing and taking care are looked down upon. As is the case across the Black Sea region, in Çaykara and on the Kuşmer Highland, too, through all these local practises which serve to reproduce life itself, dispossessed women suggest other forms of committing and belonging to both land and space, aside from ownership. As we understand, truly resisting dispossession entails creating such spaces that will give rise to independence from the market, and the many institutions and relations buttressed by patriarchy, much rather than insisting on ownership.

- Begüm Özden Fırat and Ayça Yüksel, 2024

Blossoms of Farewell, Solo Exhibition, Hara Istanbul, TR, 2024