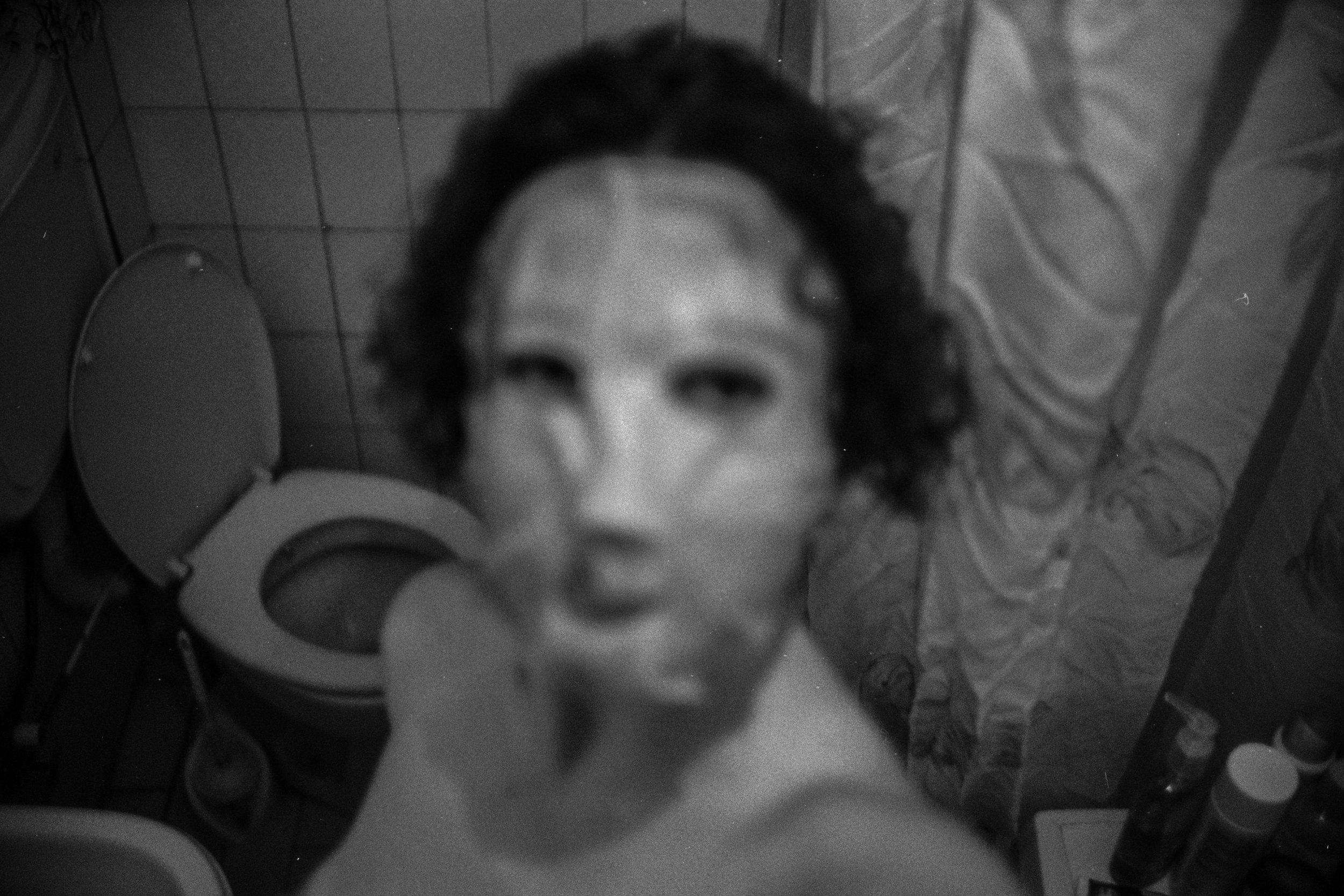

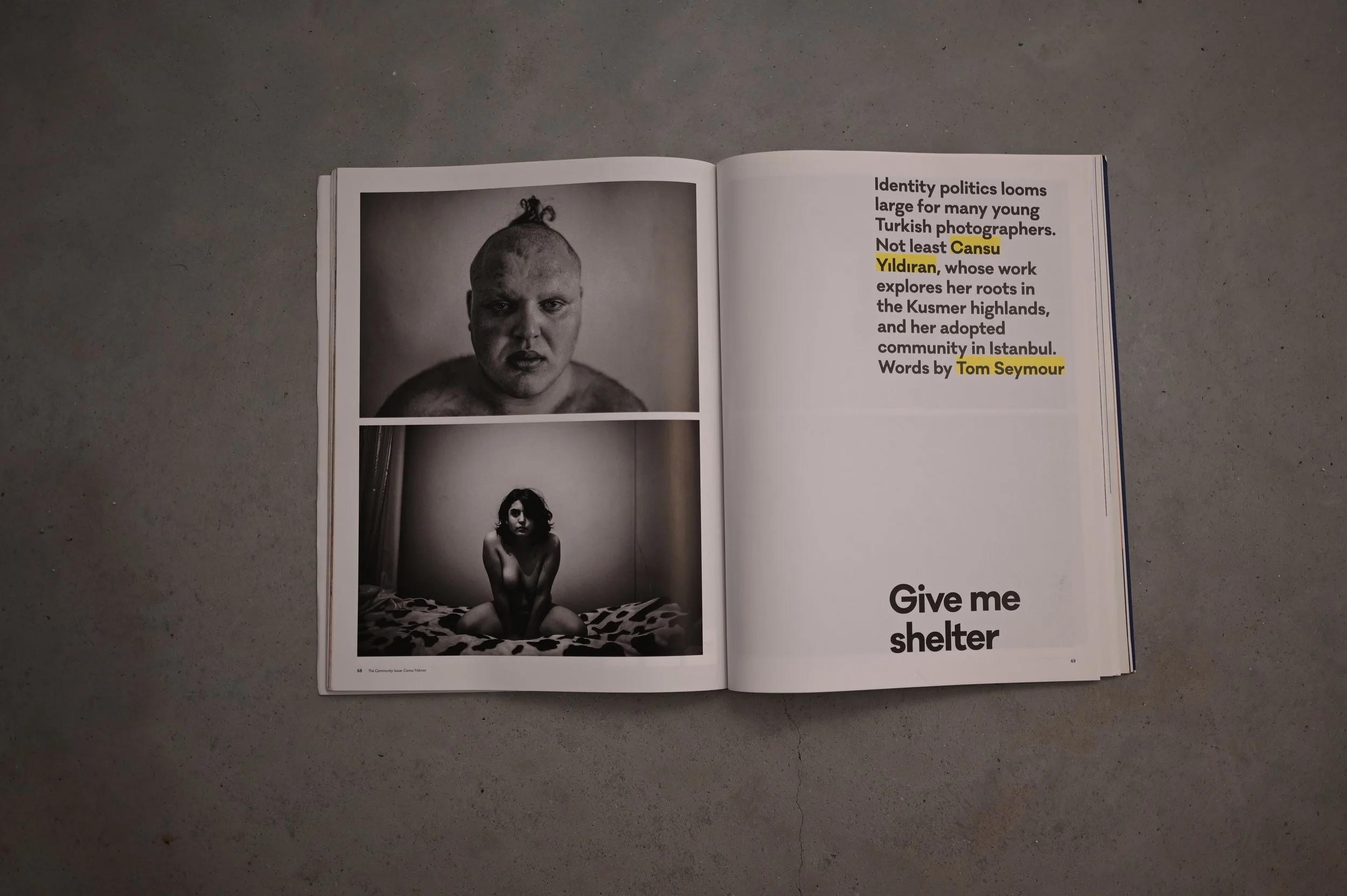

“What separates Yıldıran is her range and her style – her ability to fuse seemingly disparate images into a cogent, atmospheric whole; to capture the ephemeral and, through judicious sequencing, give them a weight and significance that might evade the image in isolation. Here, then, is a photographer capable of capturing life’s more intense, and more confusing, moments of intimacy. But – more than that – here’s an aesthete also eerily adept at using contrast, focus, saturation and exposure to impact on the shape and texture of those intimate moments. Some images are pin-point sharp, others have actively used an elongated shutter speed on a moving subject, resulting in a blurred, frenzied ghost of a portrait.”

- Tom Seymour, British Journal of Photography , 2019

“As much as it suggests 90s imagery, Yildiran’s photography is anything but nostalgic. Her images are a moving portrait of what freedom and possibility mean to Istanbul’s refuge-seeking youth.”

- Clara Hernanz, Dazed Magazine

The geography where I am from used to be considered to be the bridge between the East and the West. Now, it’s more Middle Eastern. I believe this was triggered because of post-2000s’ changing political climate as well as war and migration in the Middle East. These changes all coincided with the development and self-exploration of Generation Y which I am a part of.

As this situation affects people’s living spaces, the development process which the Generation Y goes through is also affected. Those who belong to this generation grow up in a more conservative way in Central and Eastern Anatolia, while a whole different story goes on in the West. The west of the country has a diverse population because of heavy migration from the East that is caused by war and economical problems.

Eventually this situation becomes a major factor in having an identity crisis for people of Generation Y in the West. Many people from different cultures and backgrounds migrate to the same place because of different social reasons to seek a new life by adapting to it. They carry their own backgrounds and culture with them to the place they migrate. They form a new life with the people they feel relevant to in terms of their own mindset, culture and identity.

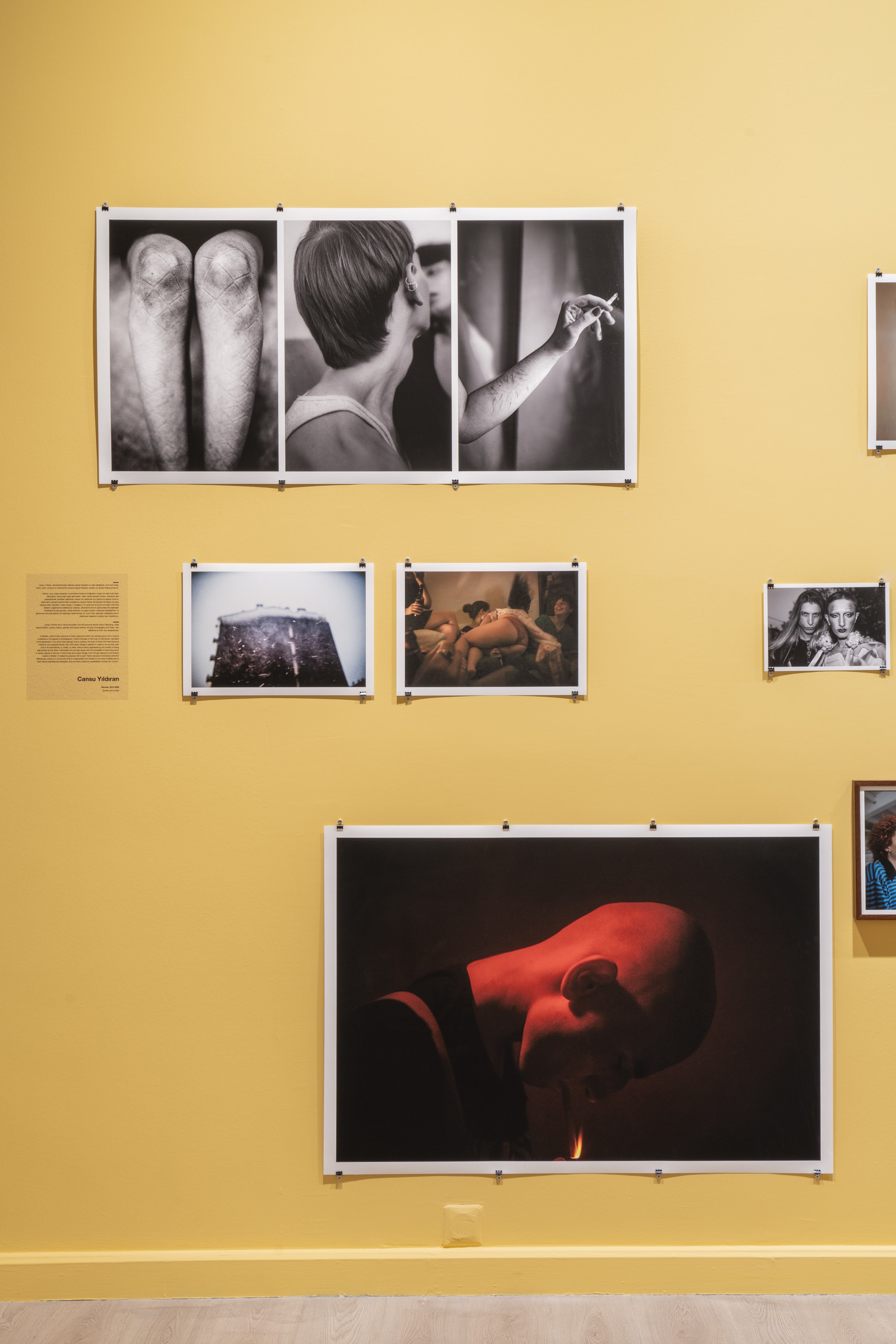

I wanted to talk about the stories of groups that were marginalized because of their sexual identities and lifestyles among the groups that could be counted as a community. One of the basic reasons for this is that I do feel as close to these communities as ways of thinking, feeling and living.

From an external perspective, the most basic concern of these groups, which are considered as utopically 'other', is to exist. The right-wing conservative lifestyle, which encroaches upon increasingly habitable areas, and the consequences of political power lead these groups and identities to further close in. Although the communities where Generation Y feels safe inside provides a space for the individuals to flourish, the same safe spaces also become cages, sheltering them from outside creating a paradox.

When these identities and communities which can be considered as safe spaces are getting smaller and smaller every day, I want to tell the process and changes of the Generation Y which has the most fluid structure of these identities.

Whose arm, which leg, where is the curtain, where is home?

Waking up to an-other collective dream

“Keep the courage that is required to maintain the norm. The cold-blooded loan of your bodies to the incessant process of regulated repetition. Courage, like violence and silence, like force and order, is on your side. On the contrary, I assert today the legendary lack of courage”

Preciado, who was invited to talk about courage as part of the festival Mode d’Emploi (2014) that took place in Lyon, wrote instead for the newspaper Libération, about the lack of courage and exposed the paramount technologies of normalization behind gender attribution: No, gender and/or sexuality were not natural characteristics of the body, but they were the products of discourses, practices and policies aimed at the administration of life and truth; products of a classification that forced itself as truth. All of these verbal or non-verbal mechanisms, while they classified the uses of bodies in categories such as natural-perverse, right-wrong, straight-homosexual, feminine-masculine, they also forced us to find a place, to make ourselves understandable, lovable, protectable and to survive within these classificatory schemes. To maintain the norm meant giving up on the possibility of being different, on the unforeseen uses of the body: The identity that interpelled us to be someone (a woman, a man) was a prison for the body.

No, the norm(al) was in no way self-evident, it took a lot of violence, a lot of surrendering and a lot of courage.

reciado thus let down those who invited him to talk about ‘the courage to be yourself’; while expected to tell the story of his transition from Beatriz to Paul as courageous, he reversed the hierarchy of feelings that put courage on a pedestal. The article ended addressing the “brave”:

“But because I love you, my brave equals, I wish for you a lack of courage; it’s your turn. I wish for you to no longer have the force to repeat the norm, to no longer have the energy to fabricate identity, to lose faith in what your papers say about you. And once you have lost all courage, drained with joy, I wish for you that you invent another mode of use for your bodies. It is because I love you that I desire you weak and despicable. Because it is through fragility that the revolution operates.”

***

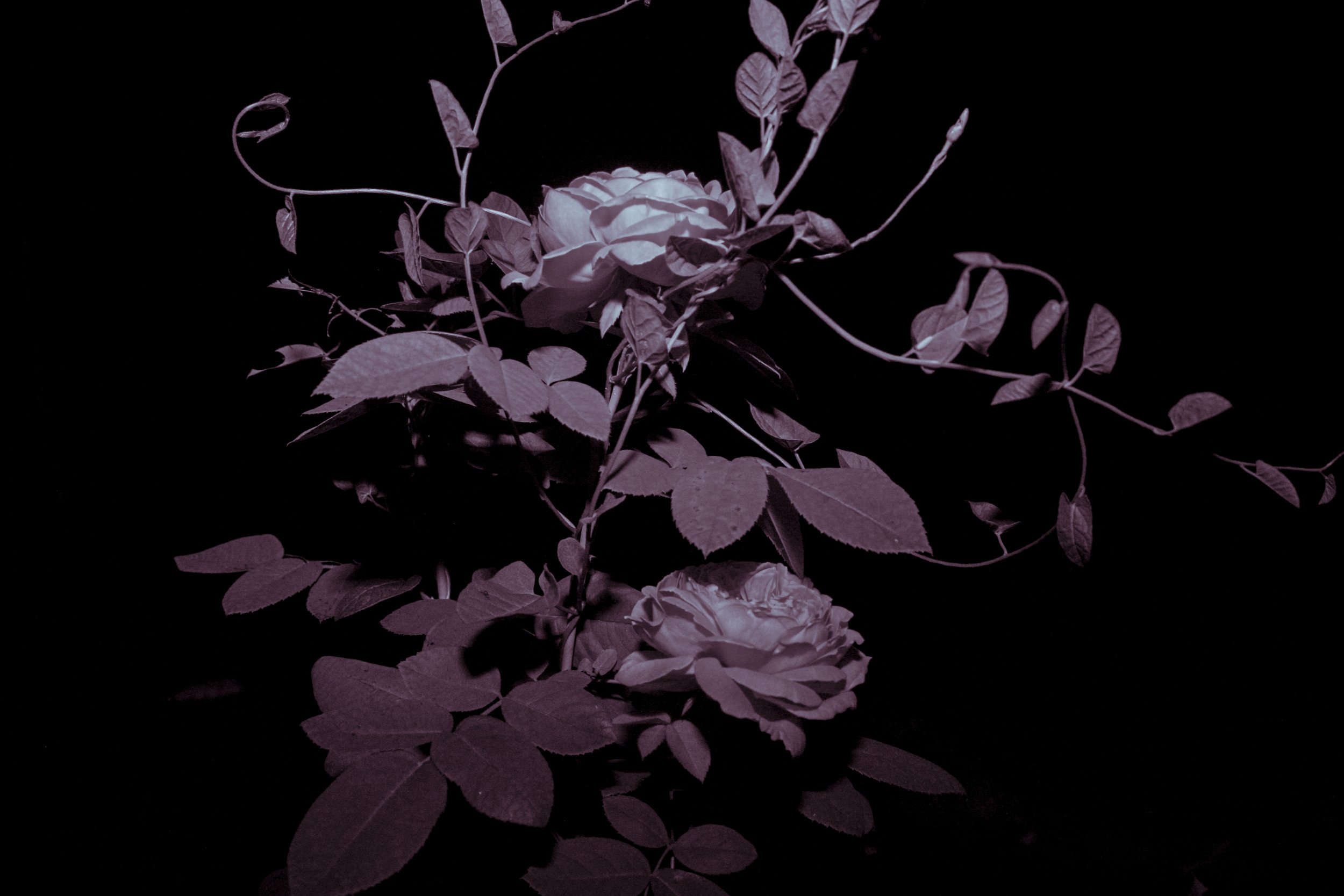

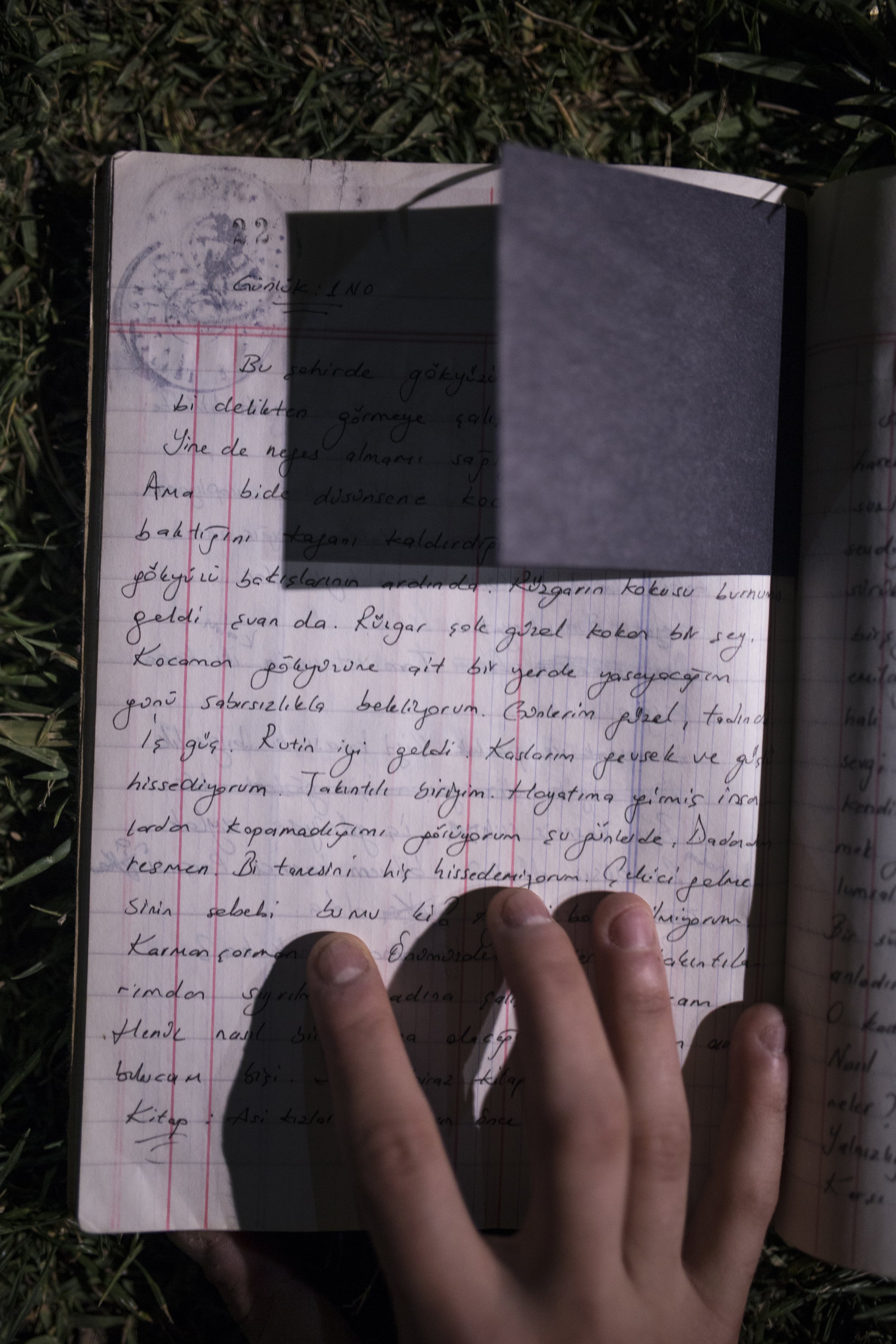

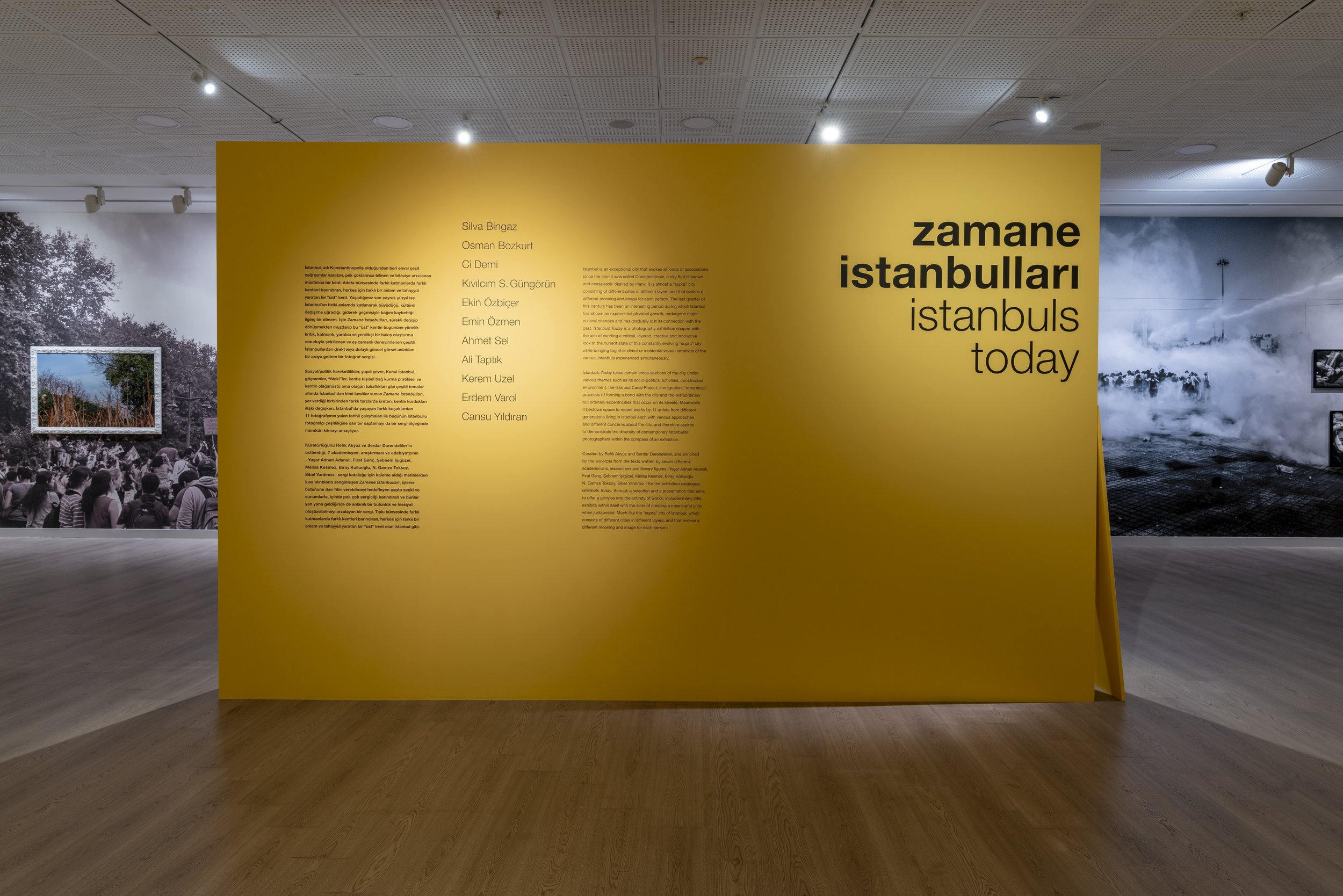

When I was invited to Cansu Yıldıran’s ‘Shelter’ as part of ‘Istanbul of Today,’ I was drifted back to this text that I have read many times with enthusiasm. ‘Shelter’ opens up before us like a big atlas of feelings and images: arms, feet, legs, hair, backs, trees, waters, liquids, hands, roses, tongues, thorns, dogs, cats, curtains; staring, abstracted, closed eyes that look in the mirror, outside, to the camera; dolesome, thinking, joyful, friendly faces; lying, standing, kneeling, wrapped, broken bodies at home, on the streets, on stage, in black, white, pink, red. We are well aware that we are seeing them through someone’s eyes. Yıldıran frames them with serenity and leaves them in our hands with care; questioning who we are interpelled to be, and to what extent we respond to this call. She suggests new ways of relating, cutting and re-stitching the body, the home and the city: Whose arm, which leg, where is the curtain, where is home?

To “come out of the collective dream of the truth of sex,” Preciado proposed to “burst the semantic field and the pragmatic domain.” This, at the same time, meant leaving altogether behind the idea of a complete and gendered body, and the language of gender difference/identity. No doubt, ’Shelter’ has its eye on this abandon: “Appear dykes who aren't women, fags who aren't men, trannies who are neither man nor woman,.” A multitude of (mostly infamous) bodies, relations of power, and a diversity of life forces travers the shelter. Yıldıran seems to be against the essentialization of homosexuality as much as they are against the naturalization of heterosexuality; they substitute the multitude of differences for biology, affinity for similarity and kin-making for genealogy. Thus, another layer in the texture and a moment of otherness in the calendar of the city is cracked open, the possibilities in the story of the ‘new Istanbul’ multiply. Since she aspired to become a global city in the 2000s, Istanbul has been terribly gentrified; class differences have marked off and reproduced space anew; while the rich and the poor were entirely separated, it has become day by day harder for the dispossessed to reach fundamental rights and any opportunity that a city can offer. Many districts such as Beyoğlu and Karaköy which were demolished and rebuilt for "the tourist gaze’" are struggling to sustain a counterfeited sterilized legacy, devoid of conflict. In the ten years following the Gezi uprising, all kinds of social and urban struggles have been targeted. The Istanbul Pride has been banned since 2014, and paraders have been attacked by the police; all kinds of rights-based gender/sexuality politics have been stigmatized by way of moralizations and silenced. With the pandemic, the majority has withdrawn from public spaces and public life.

‘Shelter’ nods at a different possibility in this new Istanbul – neither bypassing violence nor basing itself on it. Against all closures and enclosures, it climbs on rooftops, goes out to the streets, blends with waters, clouds, trees, smells; plays with the scale, mixes homes and streets; interweaves fragility and care in places we do not recognize (or do we?). Against impoverishing capitalism, isolating neoliberalism, defeating urban rent, rising conservatism and deadly violence targeting all kinds of difference, it opens up onto a different climate.

“Not with courage, but with enthusiasm and with jubilation”, it wakes up to an-other collective dream - not about the truth of sex, but about the abundance of potentialities.

-Sibel Yardımcı, Pera Museum, Istanbul of Today Group Exhibition, 2022

12.09.2024 - 31.10.2024, allerArt Bludenz, Shelter, curated by Luka Berchtold, Austria, AT

19.01.2025 - 16.03.2025, Raum für Fotografie, Coalmine, What Remains, curated by Annette Amberg, Zurich, CH