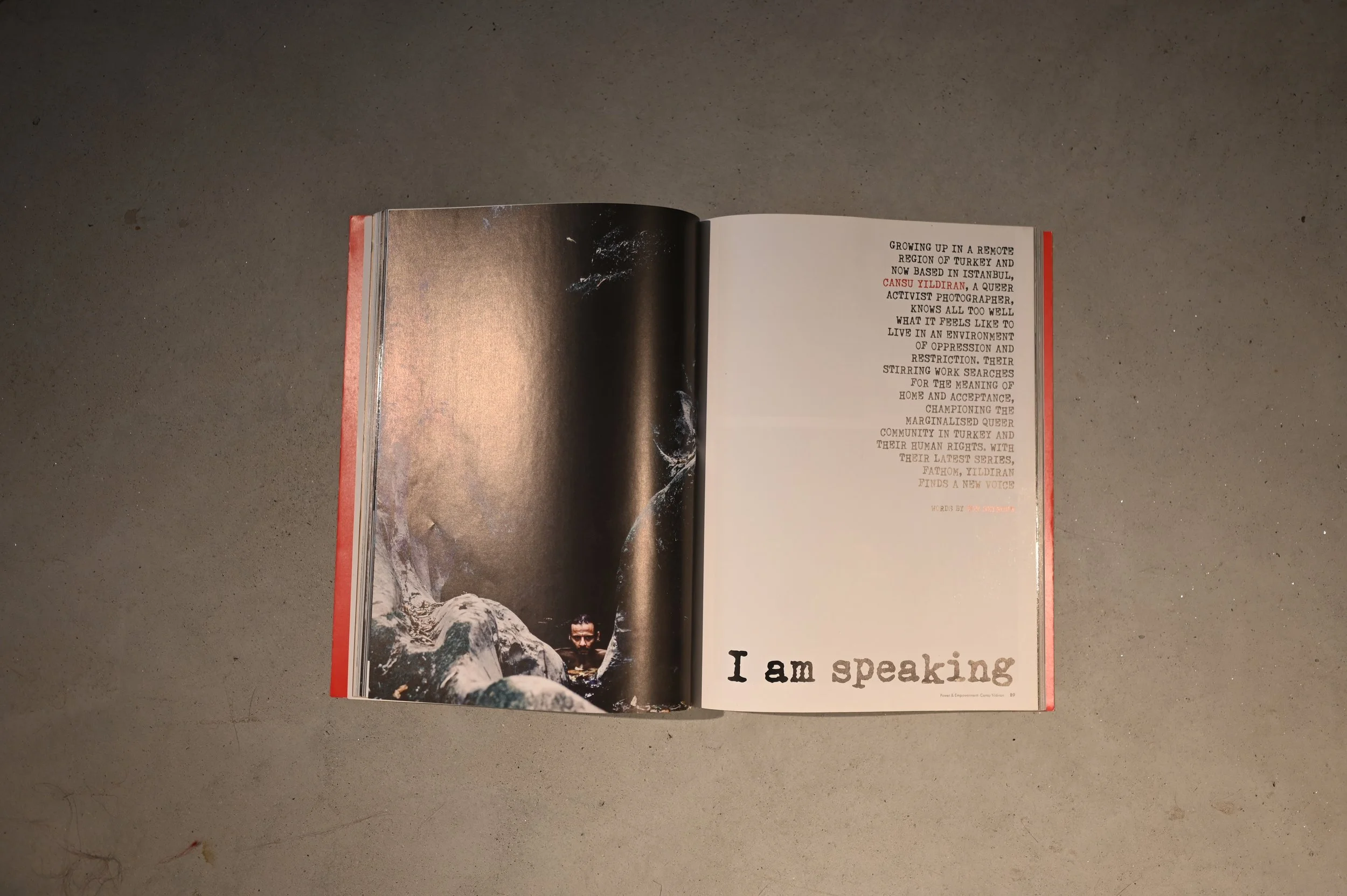

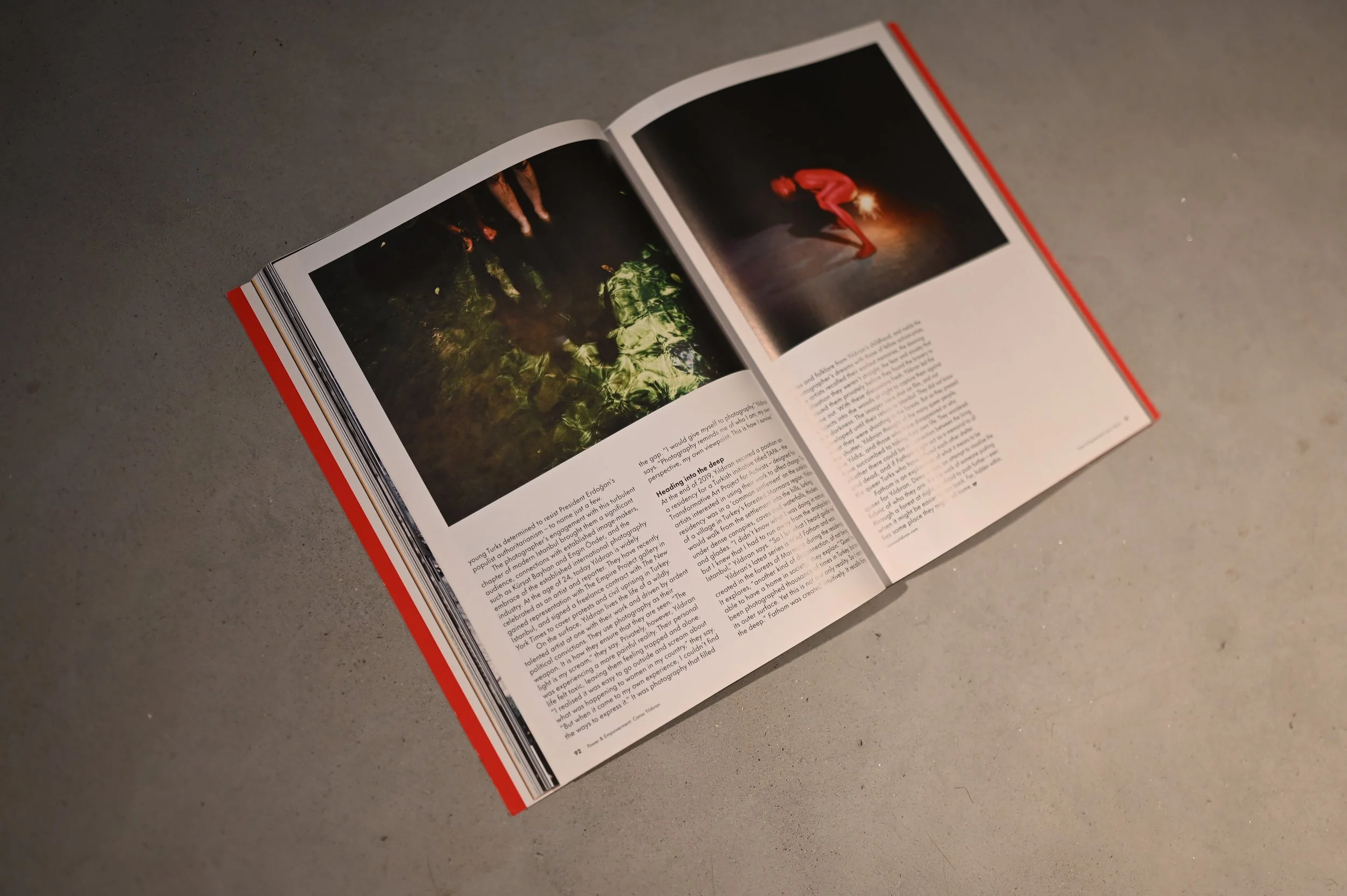

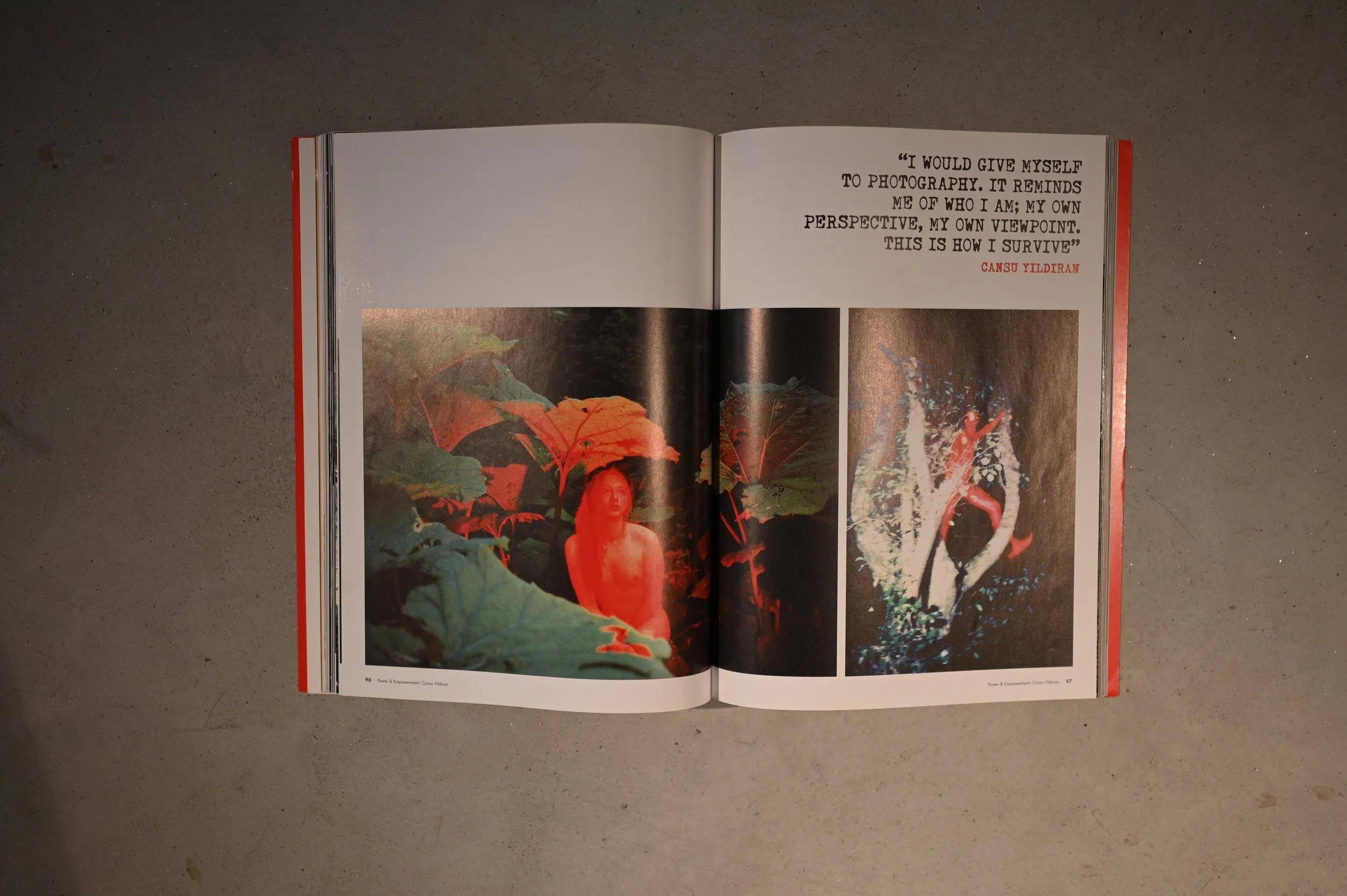

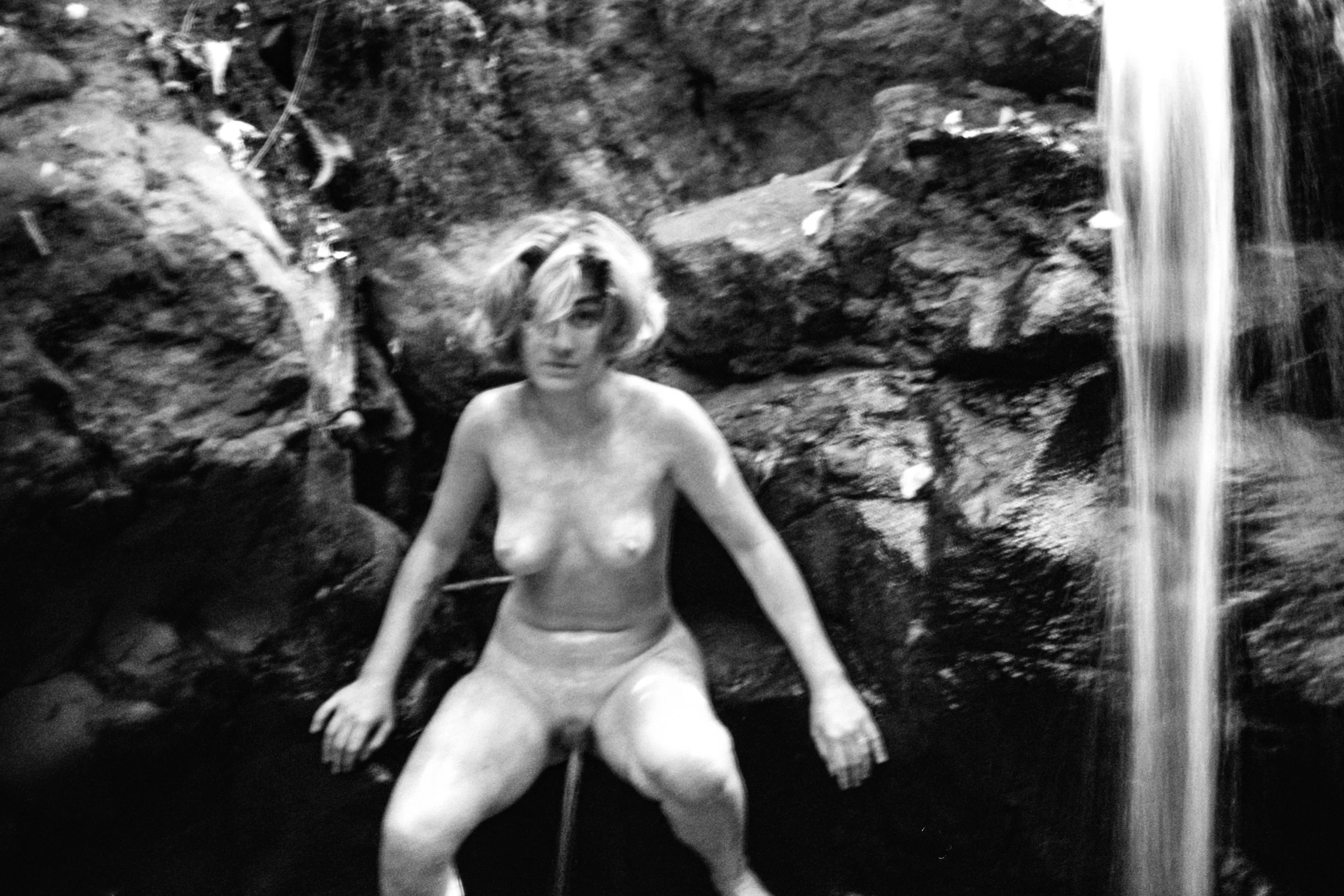

Yıldıran’s latest series is titled Fathom and was created in the forests of Marmara during the residency. It explores, “another kind of disconnection, of not being able to have a home in society,” they explain.“’Queer’ has been photographed thousands of times in Turkey, but only its outer surface. Yet this is not our only reality. So I ran to the deep.”

Fathom was created intuitively. It recalls fairy tales and folklore from Yıldıran’s childhood, and melds the photographer’s dreams with those of fellow activist-artists. The artists recalled their earliest memories, the dawning realisation they weren’t straight, the fear and anxiety that pursued them privately before they found the bravery to come out.

- Tom Seymour, British Journal of Photography, 2021

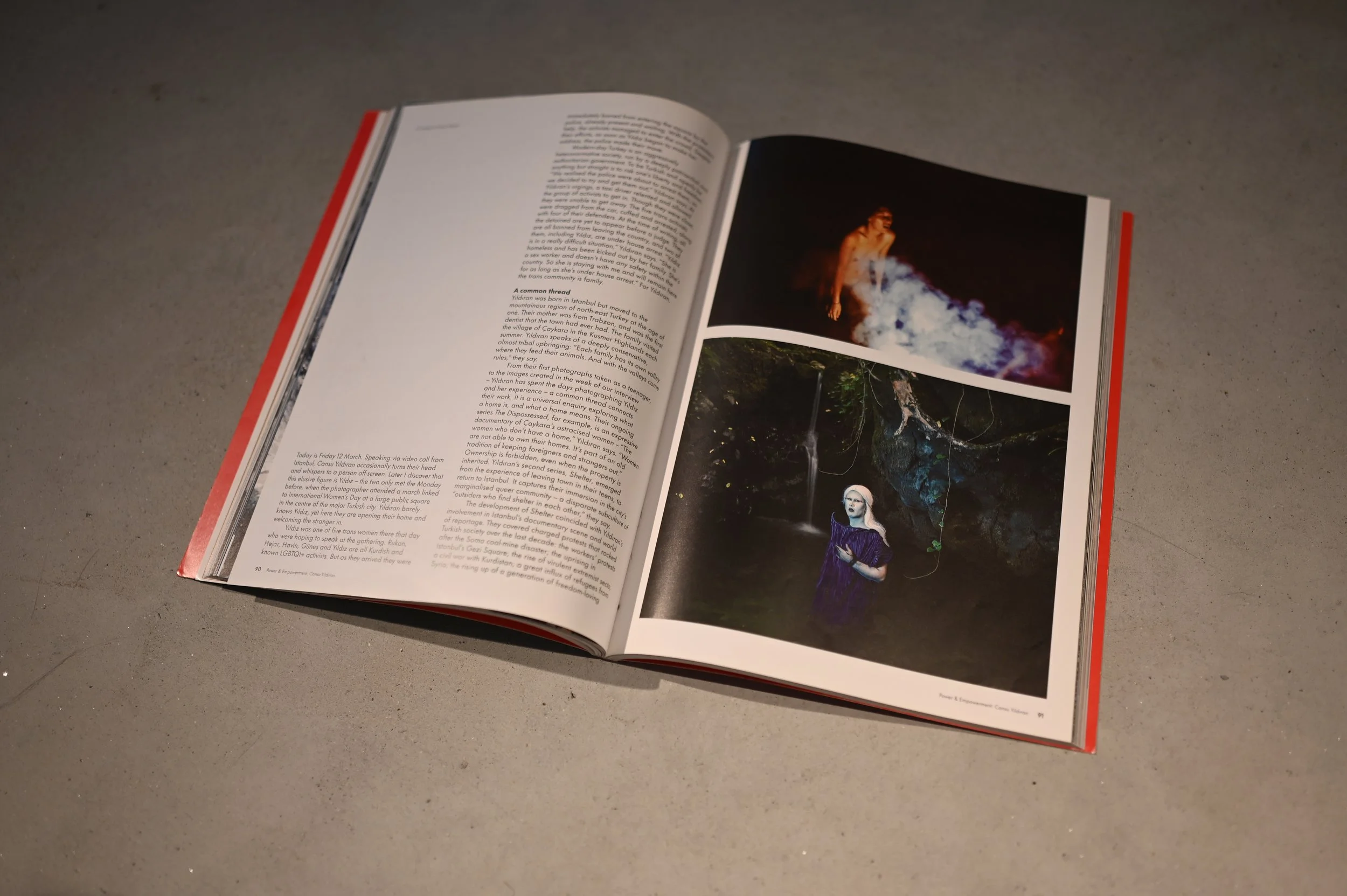

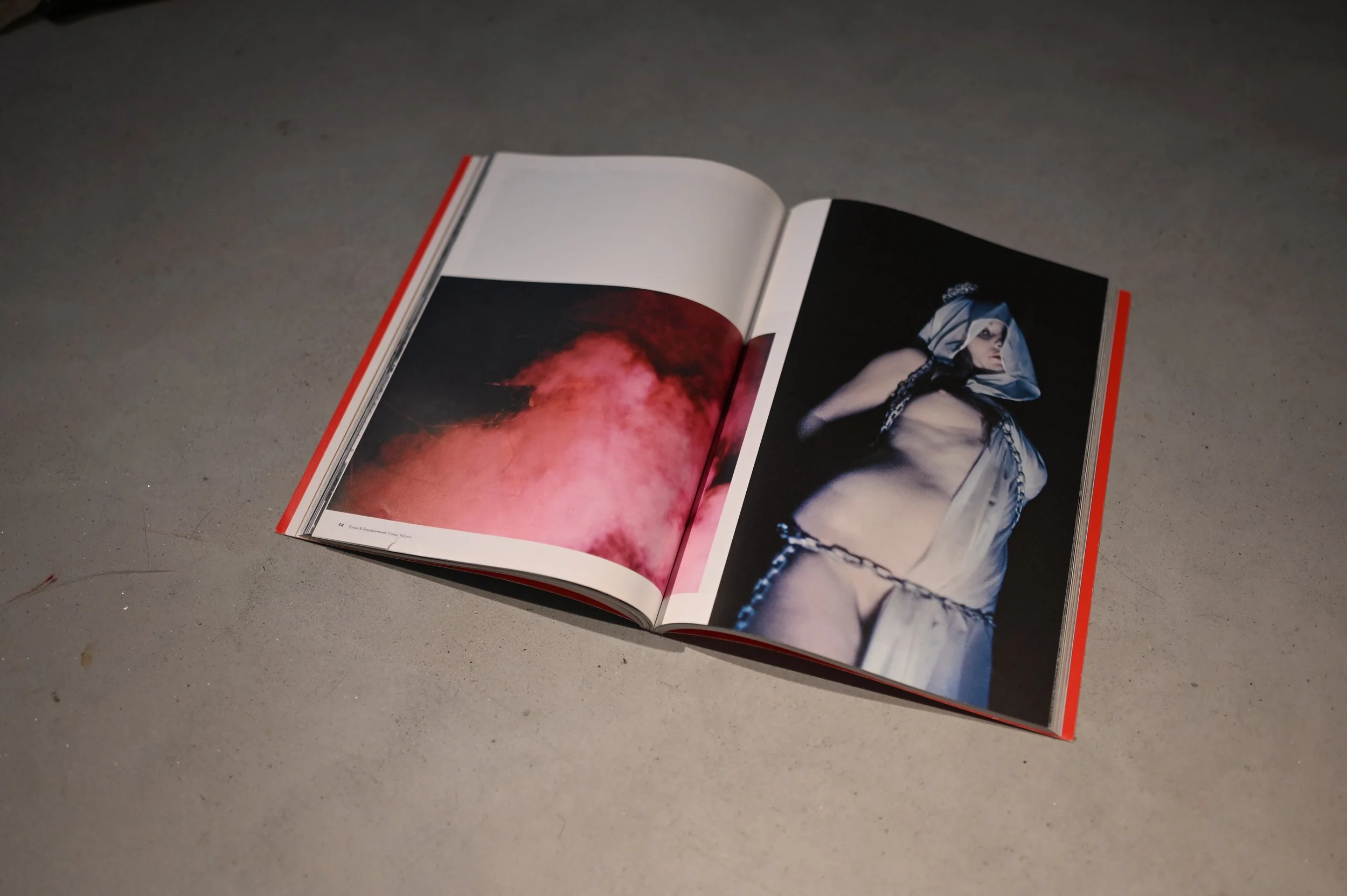

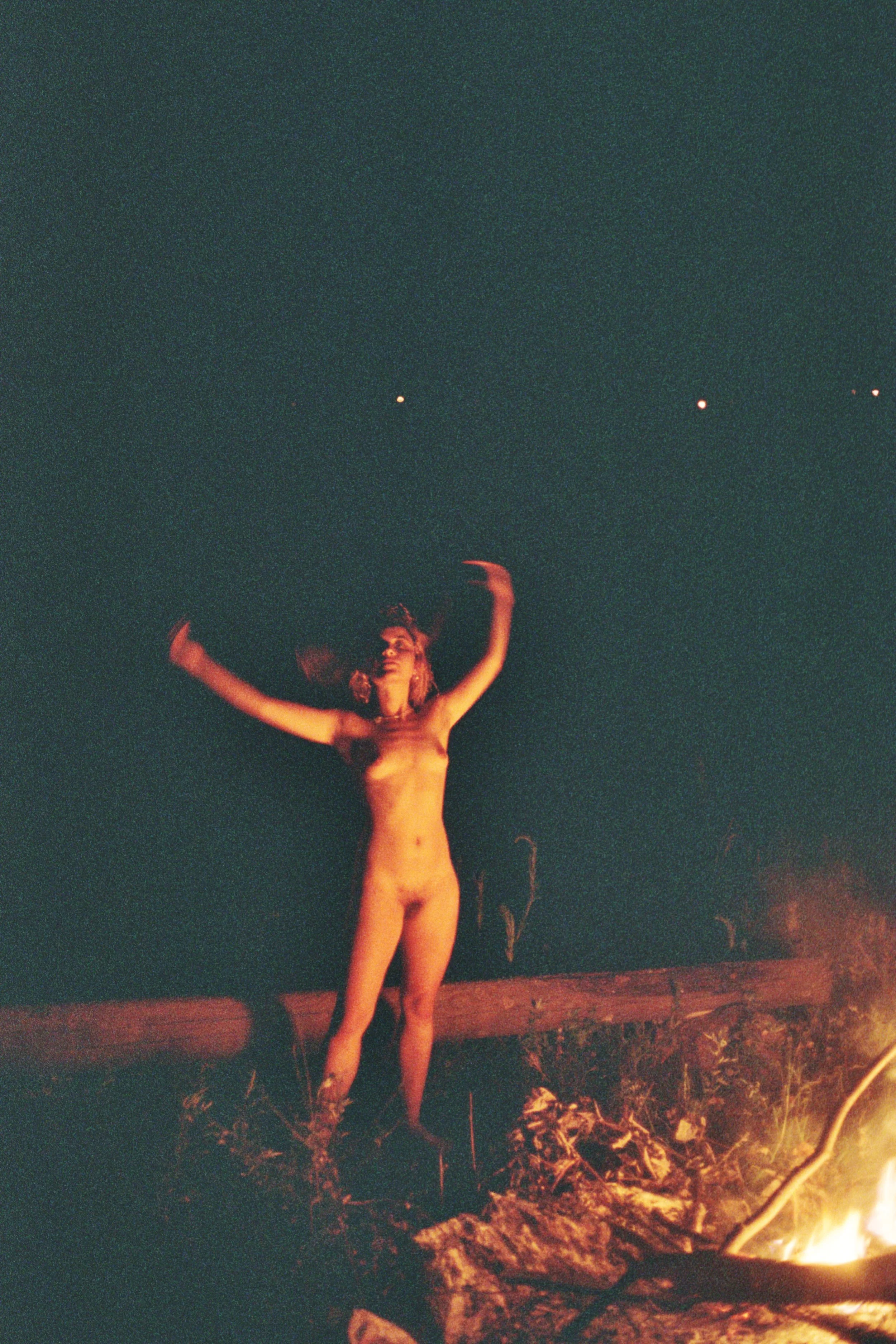

Dream-like figures appear in dense forests, dancing and floating around smoke and fires like magical figures. For Fathom, Cansu Yıldıran collaborated with fellow queer artists based in Turkey to create a fantastic world where they could feel safe and sheltered —a feeling that is often lacking in their daily life.

The dreamy visuals are fittingly accompanied by a fairytale, written by Yıldıran themselves, which tells about the heavy norms enforced on the queer community by society and how this collaborative project helped them to believe in another world, a deep mysterious realm within them.

Fathom offers an escape: inspired by their dreams and childhood fairytales, Yıldıran’s images unravel a certain state of mind, a deeper meaning of what it means to be queer within a hostile environment. The photographs are all analogue—a technical yet vital element of the project. Not knowing anything about the visual outcome during the process, it allowed Cansu Yıldıran to approach each portrait intuitively and independent of the rest.

-Winke Wiegersma, FOAM Talent Digital Exhibition, 2024

They wondered whether there could be a connection between the living and dead, and if Fathom might act as a memorial to all the queer people who have offered each other shelter.

Fathom is an exploration of what it means to be queer for Yıldıran. Deep within, an attempt to visualise the fabric of who they are. It’s the work of someone pushing through a forest at night, unafraid to push further – even when it might be easier to turn back. For, hidden within, lies some place they might call home.

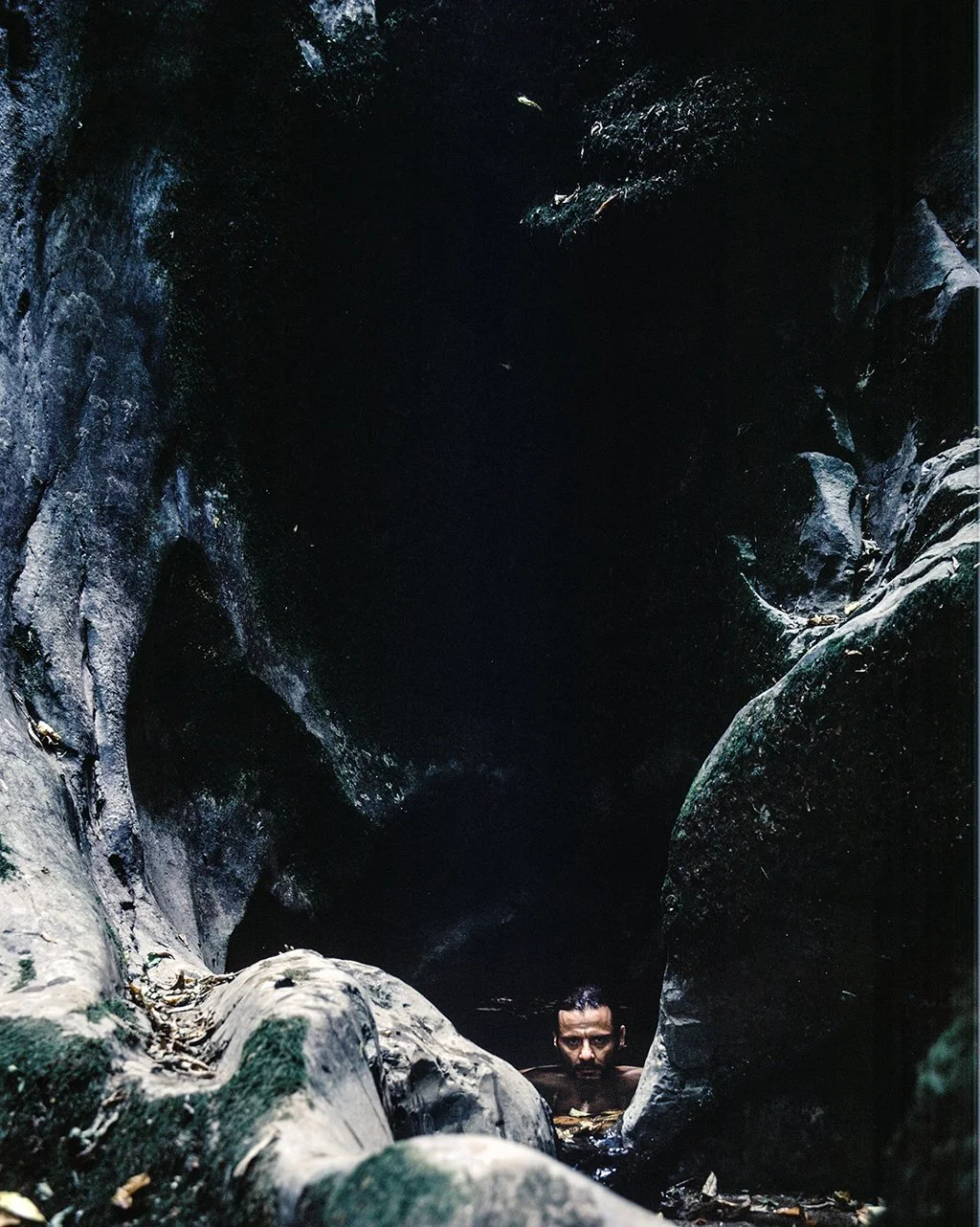

The deepest waters of the world hold mystery, because they represent the unknown. Underneath their surface, they hide different lives we cannot see through the dark. Cansu Yıldıran’s photographs are like the chapters of a feverishly documented travelogue, for which they also had to venture fathoms deep into the unknown — their own unknown, but also of others. Yıldıran’s photographs excavate fragments of queerness, unveiling the layers of what it means to be queer and performing queerness in the oppressive context of Turkey. It would be easy to just scratch the surface of a hot take on identity and show shallow depictions of either queer suffering or queer glorification. Instead, Yıldıran photographs the essence of the persons they portray by beholding them at night: when the djinns come out to play and ambiguity fills the air; when the blanket of the dark is heavy enough to muffle their whispers in lubunca, the slang that has been protecting queer, trans, and sex worker communities in Turkey from being overheard by their aggressors since the late 19th century.

The oppression and violence against queer people in Turkey are very present and vocal, yet suffocatingly made invisible too. Homosexuality is not criminalised, but still openly considered to be ‘a psychosocial illness’ or ‘unnatural’. There are no clear laws that forbid gay marriage and adoption or queer activities. Moreover, there are no laws protecting queer rights or even mentioning them. Precisely the fact that many structures and public services are available exclusively for heterosexual monogamous couples, it creates a deeply embedded exclusion of queer kinship and family in Turkish society. The presence of queer individuals is negated in Turkish law and creates judicial interpretations that crimes committed against those individuals are not hate crimes. Who doesn’t exist cannot be protected. LGBTQI+ individuals, and more specifically trans women, are targeted and subjected to extreme violence, rape, and murder in Turkey. Events that support the community are cancelled, hindered, or sabotaged. Many people have to stay hidden and find a little hole to breathe underneath a closed surface. This context often also creates problematic stories of martyrdom, exoticisation of suffering trans and queer bodies, and the portrayal of individuals as victims and victims only. Yıldıran asks themself: can there be a non-linear accounting of people’s stories, another way of retelling these past and present acts of violence and murders? Can there be a way to lift the lid of the tabooed history of more than fifty years of striding for queer rights in Turkey, without losing sight of the joy and happiness of being queer?

In their ongoing photographic series Fathom, Yıldıran portrays a community of queer artists they met during the 2020 TAPA (Transformative Art Project for Activists) residency in Turkey. This small community had the shared experience of being cruelly othered. Still, their stories about their daily lives and how they learned to live happily or exist bittersweetly within their own contexts were nevertheless very divergent. Yıldıran started photographing them, as friends and peers, during nightly sessions. Every photograph shows an individual with a name and an intimate story, who opened up and bonded with Yıldıran. Their work is the result of co-creation, a collaborative and performative practice, which relies on the enchanting results of improvisation and spontaneity. Yıldıran and their friends act wildly, as imaginary creatures, in a way that comes very close to Jack Halberstam’s definition of wildness as a space of disorder that expands after (or with) collapse, as the potential to break loose from the chains of modernity and binary capitalist culture (Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire, Duke University Press, 2020). The persons in the photographs become personas; performed versions of who they want to be and how they want to be seen beneath their surface lives. As is the case for other works in their practice, Yıldıran is seeking to create a home, a nest for a body, a community, a culture, a history through and with their photography. No amount of fathoms can suffice to measure the depth of someone’s identity. Therefore, Yıldıran and friends found solace in the creation of their own queer mythologies. They are the lubunya (queer in lubunca slang) who play in the night, stripping naked and shedding their skin, changing colours, painting the town red as they go, and creating light with burning and sputtering fires to light each other’s paths — to give hope. They learned how to hold their heads high and keep their voices low. They learned how to write their own tales and perform them. Making these queer mythologies together is not a way to defend a long past, but to imagine a queer future. As José Esteban Muñoz wrote tellingly in his book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York University Press, 2009):

‘The future is queerness’s domain. … The here and now is a prison house. … we must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds. … Queerness is also a performative because it is not simply a being but a doing for and toward the future. Queerness is essentially about the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world’.

— Zeynep Kubat, Foam Magazine Talent Issue, 2024

Verzasca Foto Festival, Verzasca, Switzerland, CH, 2025

19.01.2025 - 16.03.2025, Raum für Fotografie, Coalmine, What Remains, curated by Annette Amberg, Zurich, CH